Published June 11, 2020

Follow Filsan Abdiaman on Instagram here

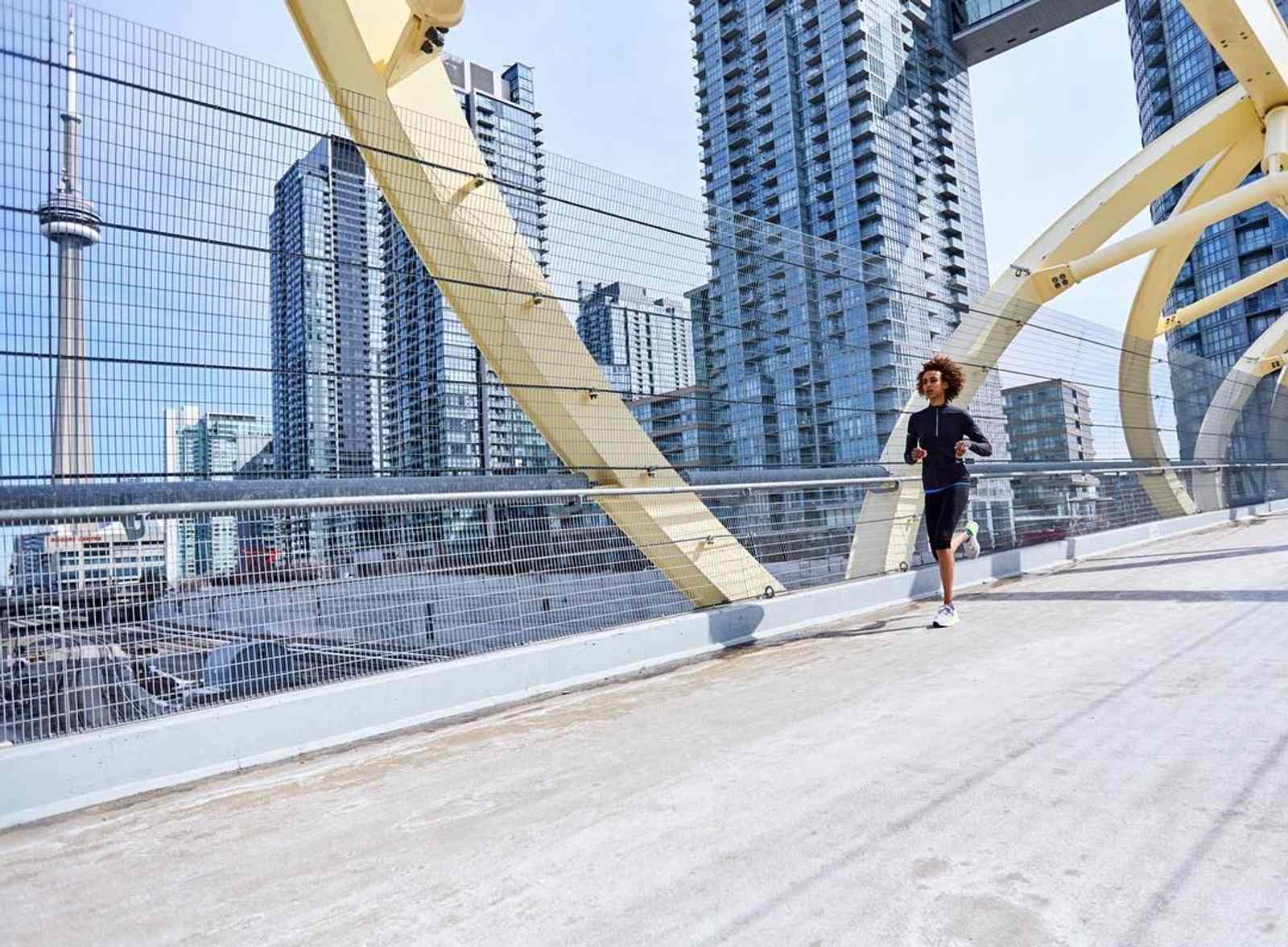

In 2013 I discovered my passion for running as a form of therapy to help deal with depression and anxiety attacks. I started with running road races at first, 5 kilometers one year, a year later a half marathon, and finally a marathon.

But I was always searching for something more, racing to beat my personal records and myself. All of that changed once I moved to Vancouver. I quickly transitioned to trail running and racing in ultramarathons.

By participating in a sport where failure is more common than success, I developed a new relationship with running. Some of my biggest life lessons I have experienced were when doing ultras.

During the Zion 100-kilometer race in April 2019 for example, when GI issues forced me to walk nearly half of the race, my slowest miles were accompanied by the clear realization that being able to run as far as I do is truly a blessing and I have to respect my body and mind every time I run.

I know that many might say this, but I believe that my story has been rather extraordinary.

Suffering from depression and anxiety is something you learn to cope with rather than overcome entirely.

I learned this lesson after developing an eating disorder in my late twenties. Ironically, this was my “peak”, when I managed to transition from road racing to trail running and ultra distances. This was also when I got to be on the cover of the Canadian Running Magazine.

Little did the world (and most importantly my family) know that at this time I was in the thralls of an eating disorder after several months of disordered eating.

It was extremely difficult to come to terms with this reality, and for the longest time, I was in denial. In retrospect, when I picked up running, I was using it to literally run away from my inner demons.

I refused to believe that someone like me—a strong black woman with deep cultural roots, that "fought depression" and accomplished so much could experience an eating disorder.

A huge part of the reason for this denial was I refused to believe I could fail. I placed a lot of pressure on holding myself up to a certain standard.

At the same time, a lack of diverse stories—seeing no one else (black women/women of colour) from my community with the same dilemma—made me feel uncomfortable to come forward.

Since most stories of athletes with eating disorders tend to focus on the experience of caucasian women, I felt left out. I believed that this was not my truth (or my problem).

It was when I had just moved to Vancouver in 2017 that I realized I needed help.

That same year, I had at least 4 different therapists (like running shoes, I juggled a few until I found the right one). Once I found a therapist I trusted, I opened up and I began to see that my cultural and religious background made it difficult to process a lot in my life, from talking about my problems with family to dealing with difficult emotions.

To give you some context, I identify as a Kenyan-Somali-Canadian Muslim woman.

Born in Somalia, I was raised in Kenya from a young age. When I was 18, I moved to Ontario, Canada. My hyphenated identity and this intersectionality had a huge influence on who I am today, as did my upbringing—a square peg in a pigeonhole type of feeling.

Growing up in a Muslim household in Kenya, I remember never having the chance to fully express myself emotionally and physically.

There were certain “welcomed” emotions such as happiness and joy, whereas any time I felt anything else, like sadness, anger, and frustration, adults around me were quick to let me know that I could get into trouble for going down that route.

My body, too, was policed in ways I only understand now. The male gaze was unwanted and as soon as I reached puberty, I was taught to cover up certain body parts that could get me into trouble.

As a Muslim girl, wearing the hijab was never enforced, but “modesty” and dressing in ways that presented you as a “decent” Muslim girl were encouraged. If pants were too tight around the hips or if your shirt fit too snug around your breasts, someone would surely let you know.

I was a very sensitive child and little did I know that this subtle form of body shaming would later impact my life and become part of the reason why I struggled with body insecurities and eventually an eating disorder.

Therapy, journaling (what I call my love notes) and yes, running–running ultras in particular–helped me heal and discover self-love.

With encouragement from my therapist, I started to write love notes to myself. My running, too, switched focus.

I went from chasing Personal Records to running to fall deeper in love with myself, my flaws… the real, true me. Running wasn’t about performance anymore. It became my meditation, a way out of my vicious binge-purge cycle.

It also became more spiritual for me, as every time I was out on the trails I felt more connected to God (you really know your place in the world when running trails).

And finding love… It’s funny how all three things, the running, my love notes, and therapy, helped bring more love into my life. I met my partner at the Diez Vista 100-kilometer in April 2018.

Out here in Vancouver, I know I run in predominantly white spaces, doing mostly trail running outside the city.

Although the trail community is extremely welcoming—a tribe of crazies just like myself–I am always aware of being the only minority. In all my races and on all the trails I run in, I am constantly on the lookout for other black folks.

As a black woman, I’ve had my share of uncomfortable experiences out on a run. As a result, I’m always vigilant every time I lace up. But I still lace up—that I do because I strongly believe that I have every right to take up space too. I have every right to show my face and presence.

Why my story and my experience in the trail running community matters is because I hope one day it can inspire the other BIPOC folks that hear it to run the trails if they want to.

Most importantly, I want those struggling with mental health and/or eating disorders to know they are not alone and to seek out help. Someone else like me has been there before and someone else might be right there with you somewhere in the world. This reminds us all of our shared narrative.

After many counseling sessions and self-work, I realized that there is no substitute for your story. I have to own my journey and that is when true self-love begins.

My running journey also brought me to a place in life where I could create Project Love Run, a women’s only running collective in four Canadian cities.

Project Love Run offers self-identifying women a safe space to come together and share stories about life stresses related to heartache, romance, body insecurities, and every other women’s issues too "scary" and "shameful" to discuss in society.

Having raced several ultra trail races ranging from 50 kilometers to 110 kilometers (I’m hoping to run even further some day), I believe I am an advocate not only for my community, but for mental health, eating disorders and self-love, always running deeper into myself everyday.