Published March 4, 2020

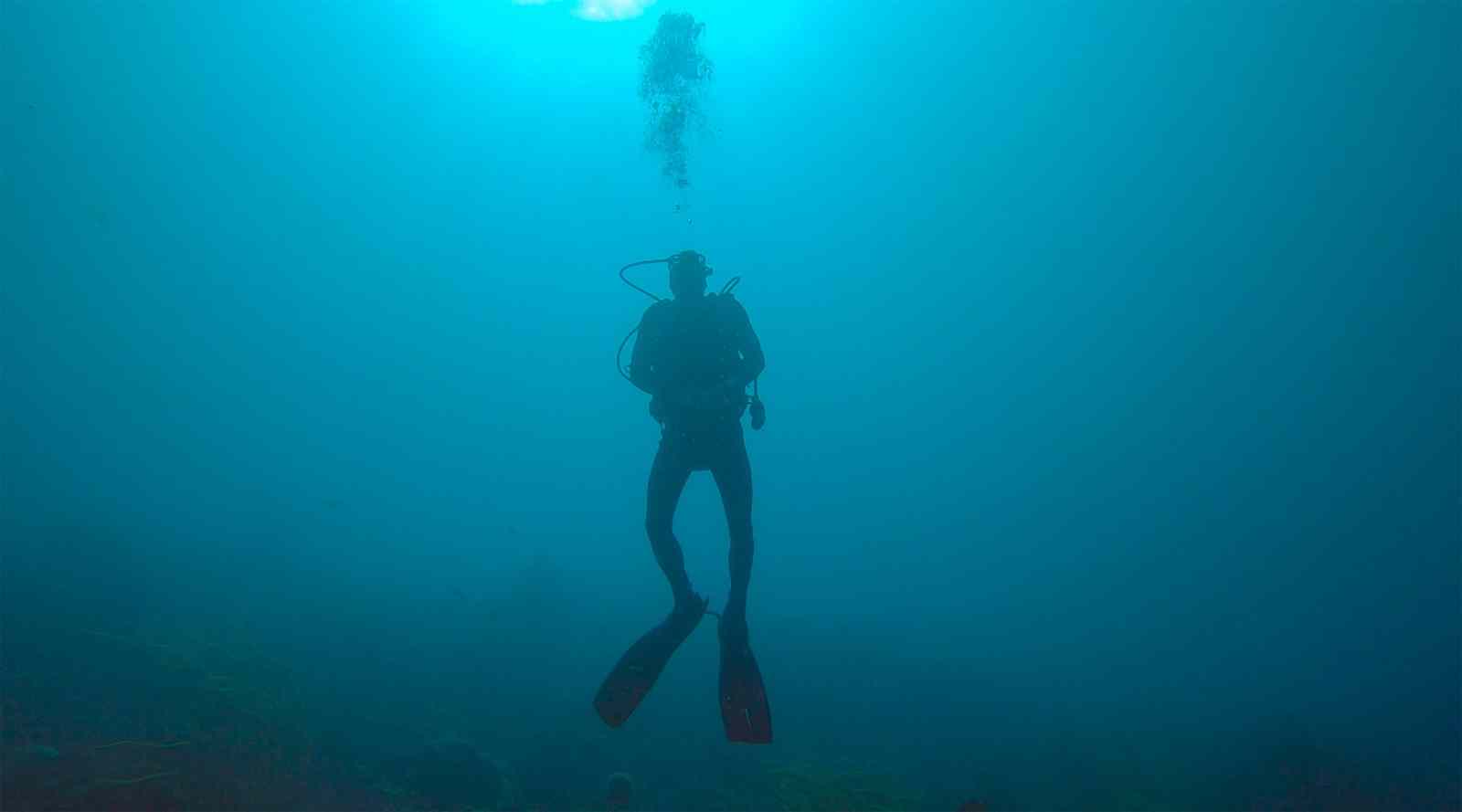

Diving to shipwrecks is a truly extraordinary experience. What could be more exciting than getting up close and personal with a real piece of history—at the bottom of a Great Lake, no less?

Shipwreck diving is eerie and educational, exhilarating and thought-provoking. It also has the potential to be extremely dangerous.

Did You Know?

Diving to a shipwreck requires training, certification, and preparation. Before you get in the water, you need to know what to do if things go wrong.

Diving to shipwrecks, like all diving, presents a number of hazards. It’s good to be aware of these risks and take safety precautions before donning your fins to explore these remnants of days gone by.

The first step of diving to a shipwreck is deciding what kind of diving you’ll be doing. How deep is the shipwreck? Will you only be diving around it? Or will you be going inside?

There are three main types of shipwreck diving:

1

Non-penetration diving

This type of diving involves swimming around the wreck. During non-penetration diving, the diver never goes inside (or even under parts of) the wreck.

2

Limited penetration diving

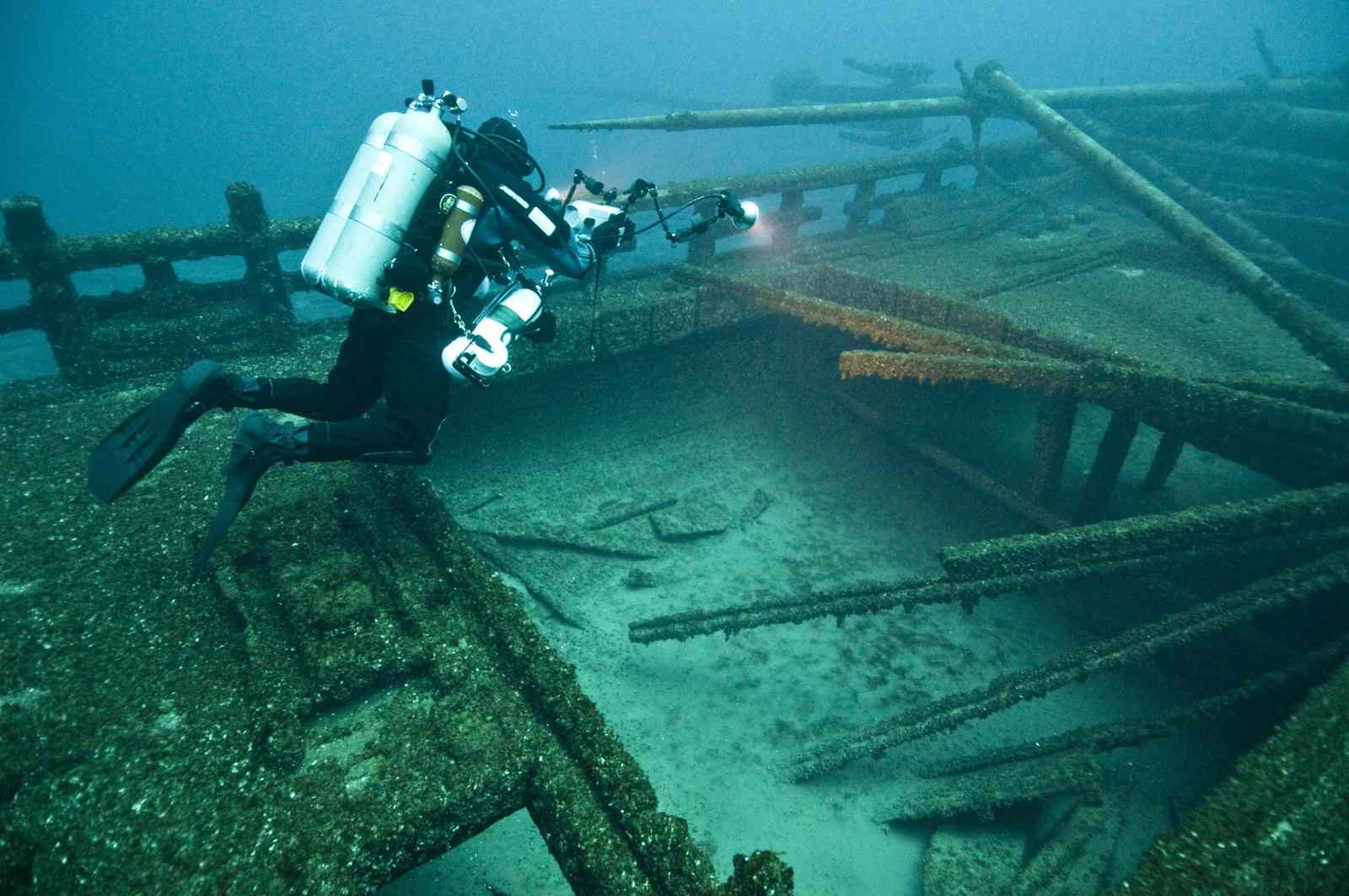

This type of diving happens in the “light zones” of the shipwreck. These zones are where natural light shines. When doing this type of diving, it’s a good idea to only enter passages with multiple points of access.

3

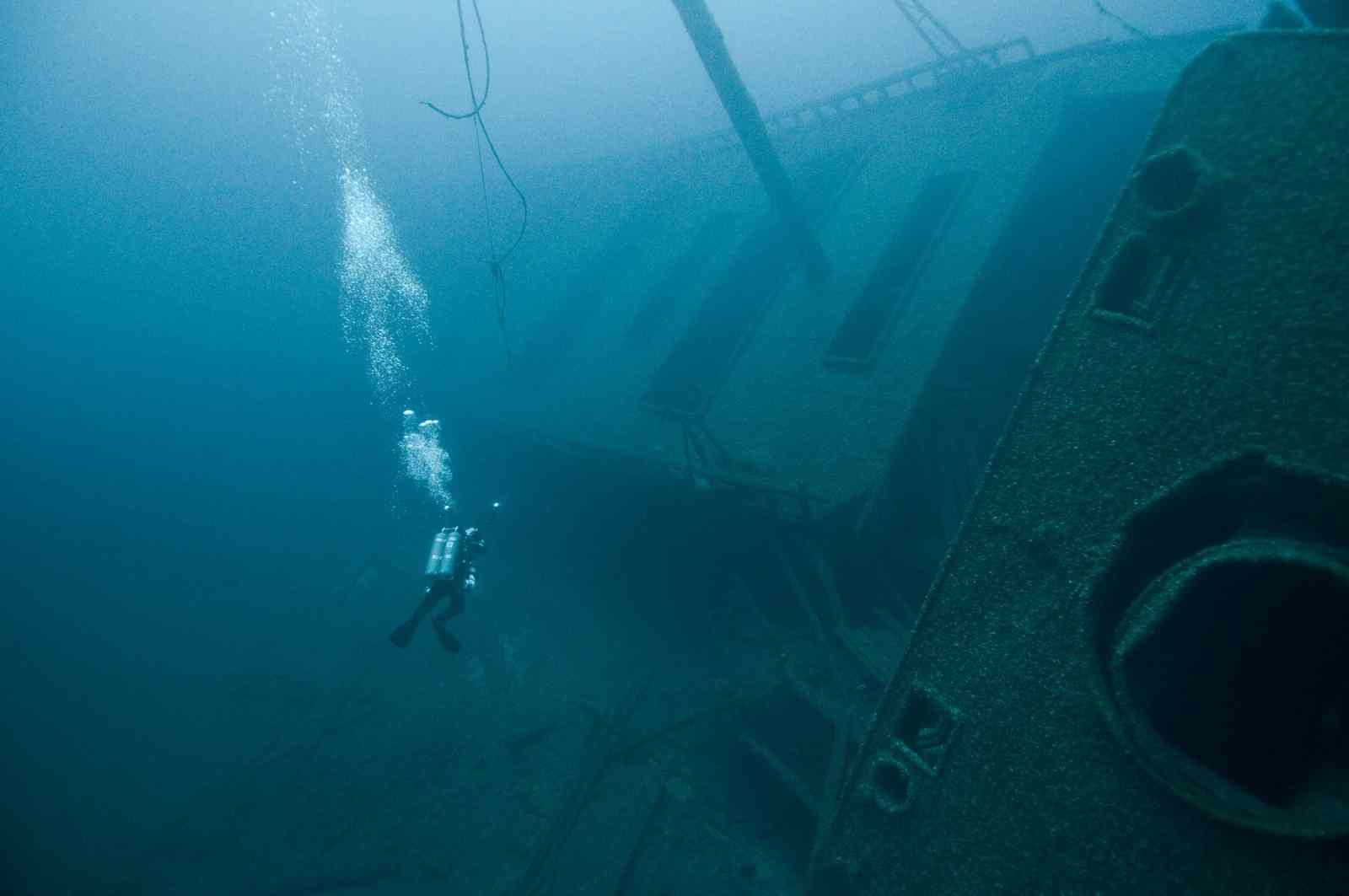

Full penetration diving

This type of diving means diving beyond the “light zone.” It is the most hazardous type of wreck diving, because you are in enclosed spaces that no natural light is able to penetrate.

Did You Know?

Here’s how to avoid (and handle) 9 shipwreck diving hazards:

1

Sharp edges or debris

Certain parts of shipwrecks can cut or snag you or your diving gear. Always wear thick, protective gloves to protect you from cutting your hands (and from cold water).

If your diving gear is cut or compromised, immediately let your diving buddy know and breathe from their backup air source. Return to the surface at a safe speed.

If your buddy is too far to help, slowly float upwards while exhaling to keep your lungs from expanding too much or too quickly. If you’re in very deep water, drop your weights for an emergency buoyant ascent (though this should always be a last resort).

2

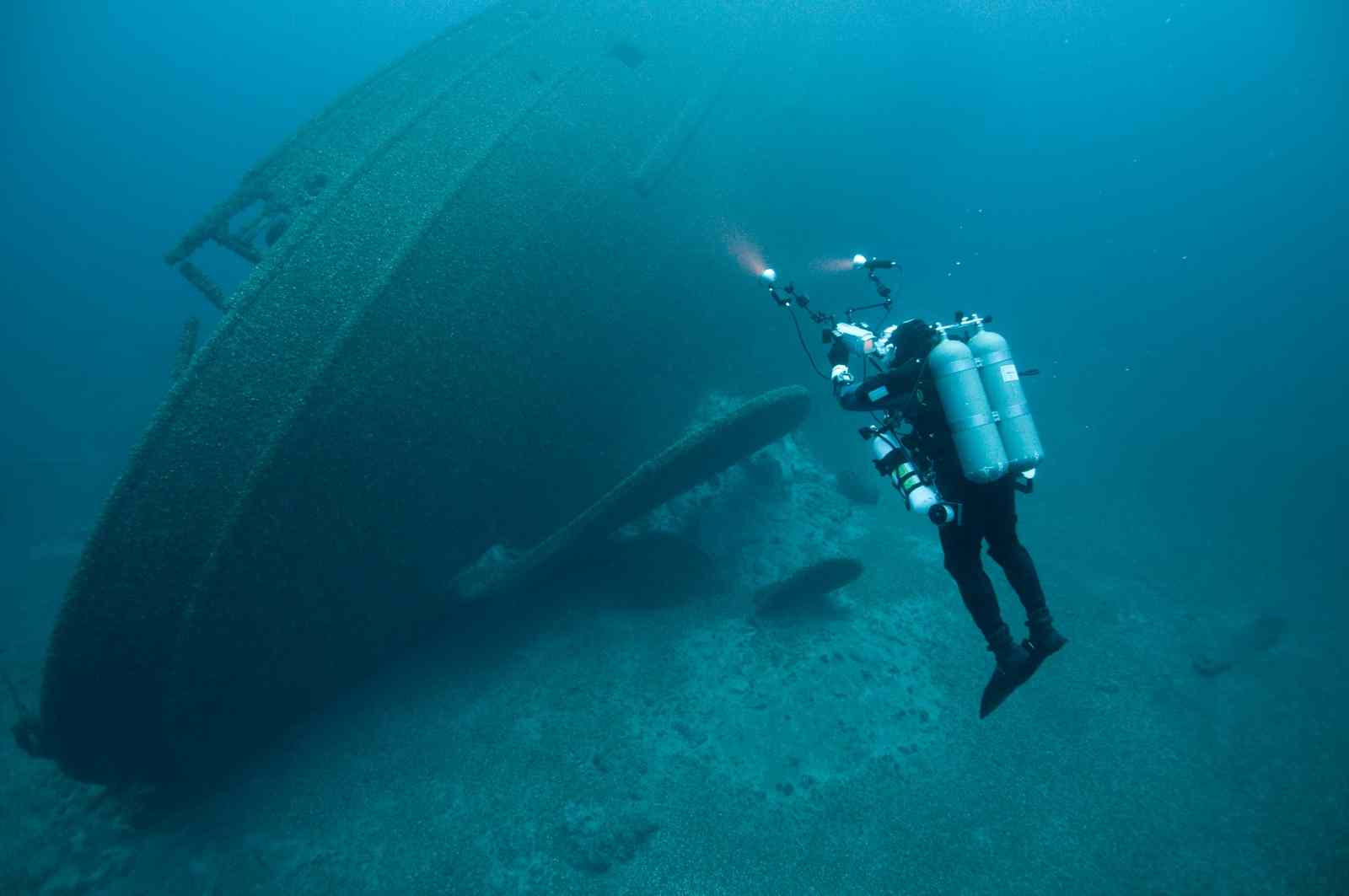

Unstable structures and falling debris

Shipwrecks can be so old they may be disintegrating. If this is the case, you can be hit by parts of the ship collapsing and you can lose exit points if falling debris blocks your way.

Avoid touching the ship, and make sure that there are multiple entry and exit points before exploring a space. Tie open doors, hatches, and other movable objects on a shipwreck so that they can’t fall or close behind you.

3

Getting tangled in fishing equipment or electrical wiring

Bring a dive knife (and a backup) to cut yourself free if you’re trapped. Be aware of your surroundings, and avoid touching nets, wiring, or other ‘tangly’ materials.

4

Losing your source of light

You may drop or break your light during the dive, so always have a spare light and batteries, especially during limited and full penetration diving. Be sure to test your lights at the surface before descending.

5

Getting lost or disoriented

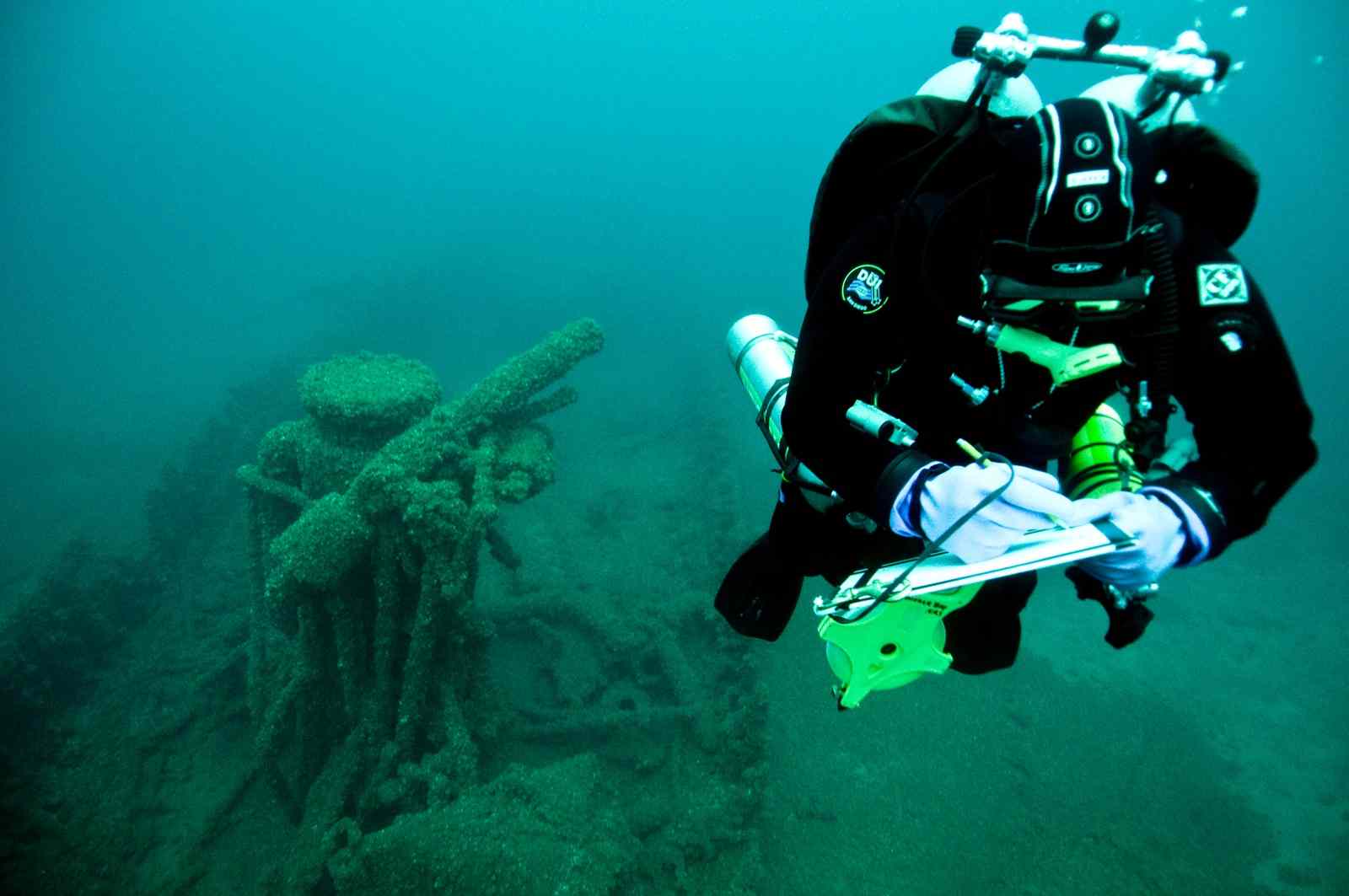

Shipwrecks are labyrinths of dark rooms and corridors. If possible, read up about the shipwreck you’ll be visiting beforehand to get an idea of its layout. Put down a wreck guideline as you go through the ship so you can find your way back out.

6

Losing visibility

When diving in or around a shipwreck, use the frog kick finning technique to avoid stirring silt, sand, rust, or other sediment.

If you lose visibility, stay near your fellow divers. Develop coded touch signals before the dive (such as a tap on the shoulder) or bring along a waterproof slate to pass back and forth for communication.

Your other gear will also come in handy. A wreck line will keep you from straying, protective gloves will keep you from touching unseen hazards, and powerful lights may be able to partially cut through the murkiness.

7

Accidentally diving deeper or farther than you are prepared for

It’s all too easy to get caught up investigating a ship.

You may lose track of time or of how far or deep you’ve travelled. The bow of a ship may be at a lesser depth than the stern (especially in large shipwrecks) and you may accidentally dive too deep. If you get distracted, you can run out of air.

If you dive deeper than 20 meters, you might experience nitrogen narcosis, also known as 'depth intoxication.' If nitrogen narcosis happens, your judgment, reasoning, short-term memory, and concentration can be affected, and you may feel like you are drunk. Nitrogen narcosis increases as you dive deeper, and the effects will be severe at around 40 meters.

It's vital that you are able to think clearly and act quickly when you're diving to a shipwreck. Always be aware of the effects diving to extreme depths will have on your mind.

No matter how fascinating a shipwreck is, always keep track of air supply, time, and depth by checking your gauge and dive computer frequently.

Did You Know?

8

Poor buoyancy control

Neutral buoyancy is important when diving to a shipwreck. It is especially important during limited and full penetration diving, when you will want to avoid bumping into your surroundings.

Before you descend, make sure that you've put on the right amount of weight. Keep an eye on your your buoyancy as you dive down, and remember that your buoyancy will change as you descend.

9

Decompression sickness

Decompression sickness, also known as the bends, is what happens when divers ascend too fast. Nitrogen bubbles build up in the diver’s body and are not expelled or dissolved quickly enough. Instead, they’re absorbed into the diver’s tissues and blood.

Decompression sickness symptoms include:

- Joint or abdominal pain

- Tingling or numbness

- Skin rashes

- Dizziness

- Headache

- Extreme fatigue

- Trouble thinking clearly

- Paralysis

- Collapse

Make decompression stops as you return to the surface of the water. This will let the nitrogen gradually leave your body. Always bring a dive table or computer so you can keep track of time and depth and avoid decompression sickness.

Shipwreck diving tips:

- Never go diving alone. Having someone with you if things go wrong may save your life.

- Don’t feel pressured by other divers to go beyond safety or beyond your comfort zone.

- Always bring extra gear. At the bottom of a lake, you’re better off over-prepared than under-prepared.

- Make sure your equipment is in tip-top shape before a dive.

- Wear a drysuit. The Great Lakes are chilly, even in the summer. The water will be quite cold when you get down as deep as the wrecks.

- For shipwreck photography, bring an ultra-wide-angle lens and a strobe.

- Read up on the history of the wreck you’re visiting to provide context and enrich the experience.

If you’re a beginner, start with a shallow shipwreck. The Bermuda in Lake Superior and the Sweepstakes in Huron are so shallow you can see them from the surface or snorkel to them.

If you will be diving rather than snorkeling, you must be certified to do so. Before you even consider shipwreck diving, make sure that you are properly trained and certified. There are many tools and techniques you need to be aware of before diving to a wreck.