Published January 30, 2020

Why does Jessi Lidstone Harewicz love open water marathon swimming?

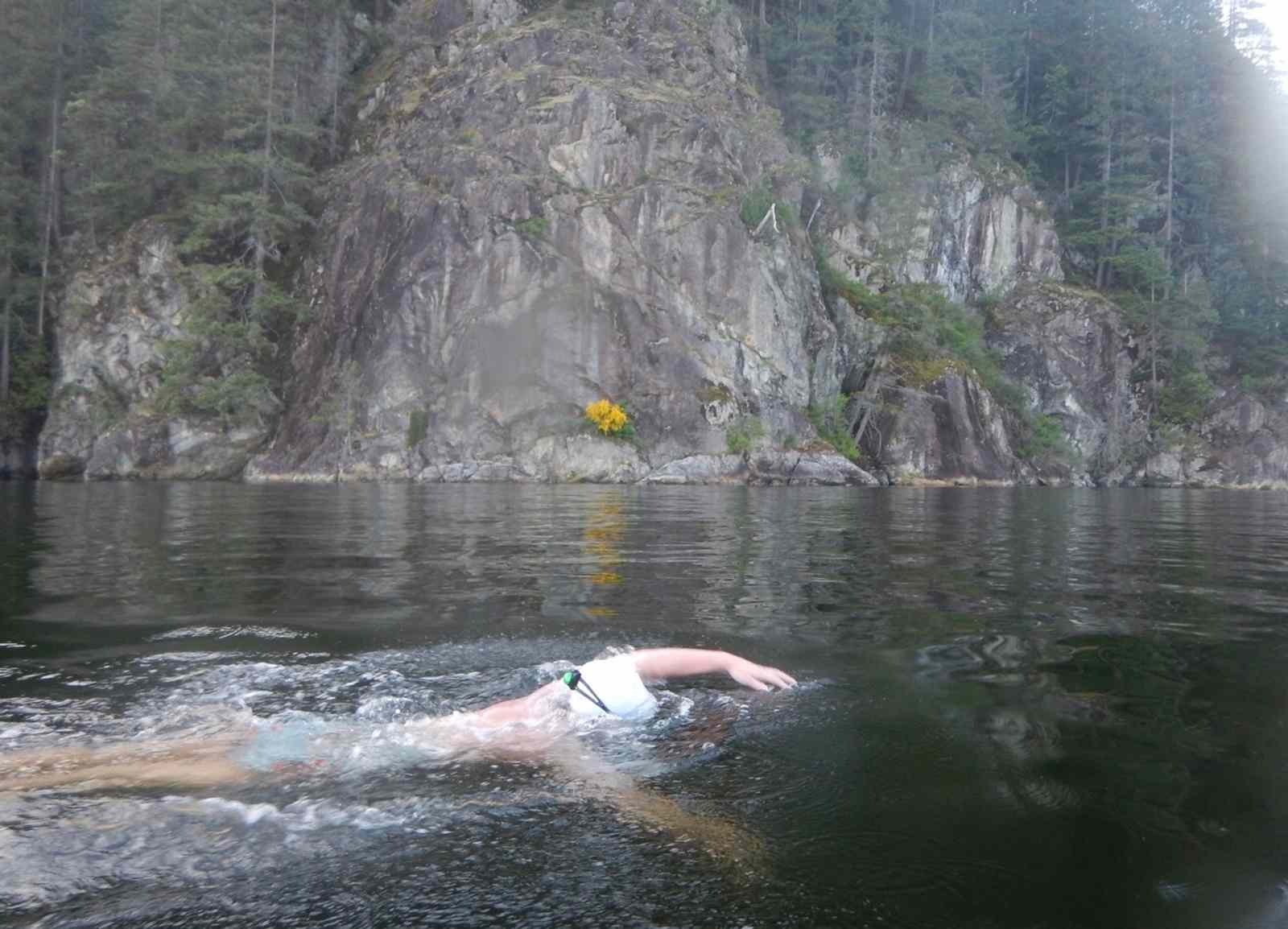

For her, it’s about getting outside. It’s about doing things that scare her. It’s about pushing herself and finding out what she can do. Plus, the majestic sight of British Columbia’s beautiful mountains surrounding her while she swims doesn’t hurt either!

Born and raised in Vancouver, B.C., Jessi grew up backpacking through Asia as a child with her adventurous parents. Vancouver was always their homebase, and it’s where she lives today.

Jessi’s parents encouraged her to find a sport at a young age. Her first foray into water recreation was doing synchronized swimming until age 15. Although swimming was never a life-long ambition in her early life, she has always enjoyed physical activity and has always led an active lifestyle.

Jessi studied Fashion Design in Vancouver and England. She has lived in many different places, from London, to New York, to Toronto, to Brisbane. She currently works in hospitality in Vancouver, and she is getting her certification in Aquatics. Jessi recently became the Canadian representative for the Channel Swimming Association.

Through hardship to the sea

According to Jessi, a lot of marathon swimmers find the sport through personal adversity. For her, this came in the form of a physical injury.

Jessi initially began ocean swimming while training for her first triathlon. Her hip began hurting within only a few months of her running training. She was misdiagnosed for almost 1.5 years before eventually being diagnosed with a degenerative hip impingement.

She cut short her triathlon adventure, but was determined to prove to herself that her life was still going to be full of adventures.

“I got my diagnosis, and they said, ‘You can’t ride a bike again.’ And I said, ‘Fine, I guess I’ll go swim the English Channel!’ I just put my head down and started tackling it after that.”

Jessi replaced trail running and cycling with open water swimming, declaring that if she couldn’t climb mountains anymore, she would learn to swim around them.

She’s inspired by the words of Irish ice ocean swimmer Nuala Moore, who says, “We can only swim the water beneath us, because we have no mountain top.”

Jessi started training with SwimTrek for the VOWSA Bay Challenge, an 9-kilometer course from Sandy Cove Beach to Kitsilano Beach. For this swim, wetsuits were mandatory. After the challenge, she never touched a wetsuit again.

She had already resolved to swim the English Channel without a wetsuit, a tradition started by Matthew Webb in 1875. Webb was the first one to make the crossing, long before wetsuits were invented. The precedent he set remains a standard for brave swimmers of the channel today. In fact, channel swimming was popular long before wetsuits became commercially available in the 1960s.

Jessi started training without a wetsuit, which was tough at first. She had to adapt and learn how to regulate her own body heat through constant movement. The results were invaluable. It was so liberating! She felt so free.

Coming home to Kitsilano Beach

As of 2020, Jessi’s favourite swim has been her most recent. On August 26, 2019, she swam the Georgia Strait, a journey that will always have a special place in her heart. This 58.6-kilometer passage took her all the way from Nanaimo to Kitsilano Beach in Vancouver.

The undertaking lasted a full day and a quarter, about 30 hours total! This extraordinary trip granted her membership into the ‘24-Hour Club’ a league of those who’ve swum for a minimum of 24 hours at a time.

Although the route was a relatively straight line, the crossing was tough and long, beautiful but wild, isolated, and challenging. The weather was unpredictable, and Jessi had to contend with fierce winds and strong currents.

This was no easy task. Open water swimmers feel weather on a microscale. Waves feel much different hitting your body directly than they do hitting a boat.

And was it worth it? Absolutely. The swim was both emotionally and physically demanding, but it brought Jessi to her home bay in the Vancouver Harbour. Feeling like she had won a day-long battle (and she had), Jessi was greeted at the shore by her friends.

“I was so excited to swim into Kitsilano beach with my dad by my side, friends support swimming, and mom at the finish! It was great bringing marathon swimming into the heart of Vancouver, proving we can do this sport in B.C., as epic as anywhere else!”

Swimming in nature's swimming pools

Being outside is an integral part of Jessi’s swimming experience. Open water swimming allows her to be adventurous and focus on her goals. It gets her outside where she can experiment with low temperatures, pushing the limits of her endurance.

Jessi believes being outside is underrated.

For her, nothing is better than the sight of British Columbia’s stunning mountain cliffs rising up out of the water, and the huge amount of coastal swimming that’s available in her city.

“You’re aware of what time the sun rises and the sun sets. Seeing the way that the sun comes up over the mountains, you realize that the sky gets lighter before the water does, because the sun hits the mountains first. It takes longer for the sun to hit the water. By spending so much time in the water, I’ve learned more about the place that I grew up.”

Swimming is a way for Jessi to disconnect from everyday commotion and reconnect with nature. In the water, she’s free from cellphones and digital clocks. She notices more about her surroundings when she’s swimming outside, and it makes her feel alive.

Swimming with Seals

Marathon swimming exposes swimmers to the constantly changing ecosystems that they visit. They are exposed to the elements, to temperature changes, to jellyfish. It’s tough sometimes, but the rewards are immeasurable.

“There are beautiful sea urchins that grow over the algae-covered rock face that glisten within the depth that the sun can reach through surface. Red and purple starfish lie lazily in the shallows around rocks in the intertidal zone. The kelp beds grow long and strong near the Point Roberts shore.”

During her circumvention of Bowen Island, Jessi recalls swimming against endless currents with taunting purple starfish beneath her. She remembers hearing them whispering and laughing at her (though she admits she may have just been hallucinating).

These visual distractions have gotten Jessi through many long, seemingly never-ending swims, even when she’s extremely nauseous and wants to quit. She feels so lucky to have so much beauty around her.

Jessi acknowledges that open water swimmers are only visitors in the waterbodies they train and compete in. The spaces really belong to the marine life living in them. She’s had days swimming head-to-head with the seals and starfish and she’s felt the odd zap of jellyfish.

On a beautiful rainy day in May, 2017 Jessi was training for the English Channel, swimming from the east side of Indian Arm from Belcarra Park up to the Twin Islands.

As she and her companions returned to Bedwell Bay, they ran into about three dozen seals. They were everywhere! Jessi describes the experience as “magically frightening.” They tried to snap a few pictures, and continued to swim through them. Nature at its best!

“By the RVYC docks, the seals occasionally swim under me, belly to belly. I see the beautiful glistening of whitey, silvery flashes under me. One time, years ago, a young seal followed me to shore at Jericho. It was so heartbreaking to leave.”

These are the moments Jessi lives for. These moments happen when it’s quiet, and no motors are around.

She can hear the water much more clearly. The audio volume underwater intensifies. At times like this, she can’t even hear her dad calling her to the boat for a feeding. Her mind just gets so wrapped up in the sound of the water.

Keeping her water swimmable

As an open water swimmer, Jessi cares about clean water. She recognizes the importance of using our waterbodies with as little impact as possible.

That’s why she partnered with My Sea to Sky, an environmental organization that works to defend, protect, and restore Howe Sound, a channel just northwest of Vancouver. The organization campaigns against unsustainable industrial projects that threaten Howe Sound’s environmental restoration, and works to minimize human impacts on the area to safeguard its natural legacy.

“Our water has finally gotten clean after God knows how many years of pollution, and we don’t want to backtrack.”

Jessi has swam through garbage in lakes, particularly lots of cans. She mentions that above all, noise pollution is what she notices the most: cars, boats motors, and airplanes. Once she gets out into the ocean, she notices surface debris instead, such as floating driftwood, which can be dangerous.

During her swim around Manhattan in New York, Jessi was pleased to notice that the natural parts of the city still exist, and that they actually coexist with the urban cityscape. She explains that the Harlem River was industrial with lots of train bridges, but that as she moved north, the landscape became more natural, with parks and cliffs.

Will we ever see Jessi on the Great Lakes?

Jessi says that a big part of marathon swimming is planning her next swim. Citing advice from one of her marathon swimmer friends, Jessi always picks swims that mean something to her. After all, she imparts, “We pay to do this. We pay to put ourselves through torture.”

And that’s the reason that you need to have a good reason to set out on a swim: when the going gets hard, you have to remind yourself why you’re doing it, and tough it out.

Jessi’s already accomplished a few of her dream swims, but she’s far from finished.

Although she hasn’t gotten to swim in the Great Lakes yet, they’re on the long list of waterbodies she’d like to explore. Her mother is originally from Dundas, ON, and Jessi sees Lake Ontario in particular as a Canadian staple. She says swimming in this lake is something that she will do one day.

“You have to work harder in lakes than in oceans,” Jessi informs. Jessi has noticed that the salt/freshwater balance is constantly changing in the Salish Sea. Swimmers float more in saltwater, and less in freshwater. The salt content in saltwater helps with floatation, so freshwater makes staying afloat a little more difficult.

The phenomenon is less apparent in a wetsuit, where your body is supported by the neoprene. Swimmers who swim without wetsuits, like Jessi, feel the difference more strongly.

That said, Jessi also notes that swimmers tend to get less ill in freshwater because of how little salt it contains. When swimming, there’s no way to avoid inhaling or absorbing some of the water, and Jessi admits that she got chronically ill from swimming in the salty sea during the first year of her swims.

High on the list of swims she’d like to complete is the 2021 North Channel swim, a 34.5-kilometer voyage known for its ever-changing weather, strong currents, and rough seas. This swim is about the same distance as the English Channel (a swim Jessi has done), with the additions of colder water and hundreds of lion’s mane jellyfish in the summer.

“I thought swimming the English Channel would change my life. I thought I would get a moment of being reborn, or whatever. Instead, I just realized I wanted to swim more.”

Jessi would be the first Canadian to swim across the North Channel. She is quick to clarify that this swim is “super scary” and “super cold,” but she likes doing things that scare her a little bit.

In her eyes, open water swimming is about pushing yourself and taking calculated risks.

Inside the mind of a marathon swimmer

What’s going on in a marathon open water swimmer’s head during these taxing swims? If you ask Jessi, “Everything and nothing.”

Open water marathon swimming is a kind of forced meditation. She explains that in the water, things move more slowly. You become more mindful of your surroundings. When she returns to land after a long swim, her sense of reality feels altered, as if some strange drug is causing her phone to move so quickly.

In the water for so long, your mind wanders. Jessi knew a 17-year-old swimmer who did math calculations in her head to pass the time. Others sing songs.

Jessi reveals that eventually, you’re going to start feeling sick, or gross, or negative, and get to a point where you don’t know if your pain is in your head or in your body. Spending so much time in the water will bring anyone to what she describes as a “deep, dark place.” The hardest part is getting yourself past this headspace.

“You may get super bored, or start to feel really low. It’s about getting yourself out of that ditch, and understanding that your suffering is not going to last forever.”

Mental and physical endurance

Open water marathon swimming takes training, work, time, and patience (in addition to acclimating your body to hours spent in extremely cold water).

Jessi has days where she doesn’t want to get into the frigid ocean. She has days where she doesn’t necessarily feel amazing or euphoric when she comes out. Perhaps one of the most challenging parts of swimming is not letting these days discourage you.

Mental failure is a facet of the sport that is not often mentioned, but Jessi believes mental endurance is every bit as important as physical endurance. And she would know––she’s witnessed world-class swimmers abandon the English Channel swim within a kilometer of finishing.

“I’ve seen elites, guys three times faster than me, that can’t make it across.”

Jessi also brings up an emerging debate in the marathon swimming community: Do you need to be an incredibly fast, elite person to complete these challenges? Or do you just need the right support system and the right people around you?

Do you just need to work your butt off, and fail your butt off, and keep going because it’s the only way to succeed as someone who’s an amateur swimmer?

Jessi notes that there’s been growing research into how and why women are able to outlast men in sports that continue for over 24 hours.

Success is not always about the quantitative results, Jessi points out, even though this is usually how it is measured by society. She explains that you’re not necessarily going to see results immediately, as is the case when taking up any sport or skill.

Part of the struggle in open water swimming is being stubborn and determined. It’s about allowing yourself time not to see results, and persevering regardless.

“It’s about fighting through it. It won’t last forever. Nothing lasts forever. You’ll hit land eventually, you just have to believe that you will.”

To learn more about Jessi’s home beach, visit Swim Guide.

Learn 3 things to remember for open water swimming here.

Read our other open water swimmer profiles here:

Open water swimmer profile: Robert McGlashan

Open water swimmer profile: Mauro Campanelli

Open water swimmer profile: Catherine McKenna

Open water swimmer profile: Bryan Finlay

Open water swimming profile: Greg Maitinsky