Published October 28, 2019

During the prohibition era, a small, isolated island on Lake Ontario played a big role.

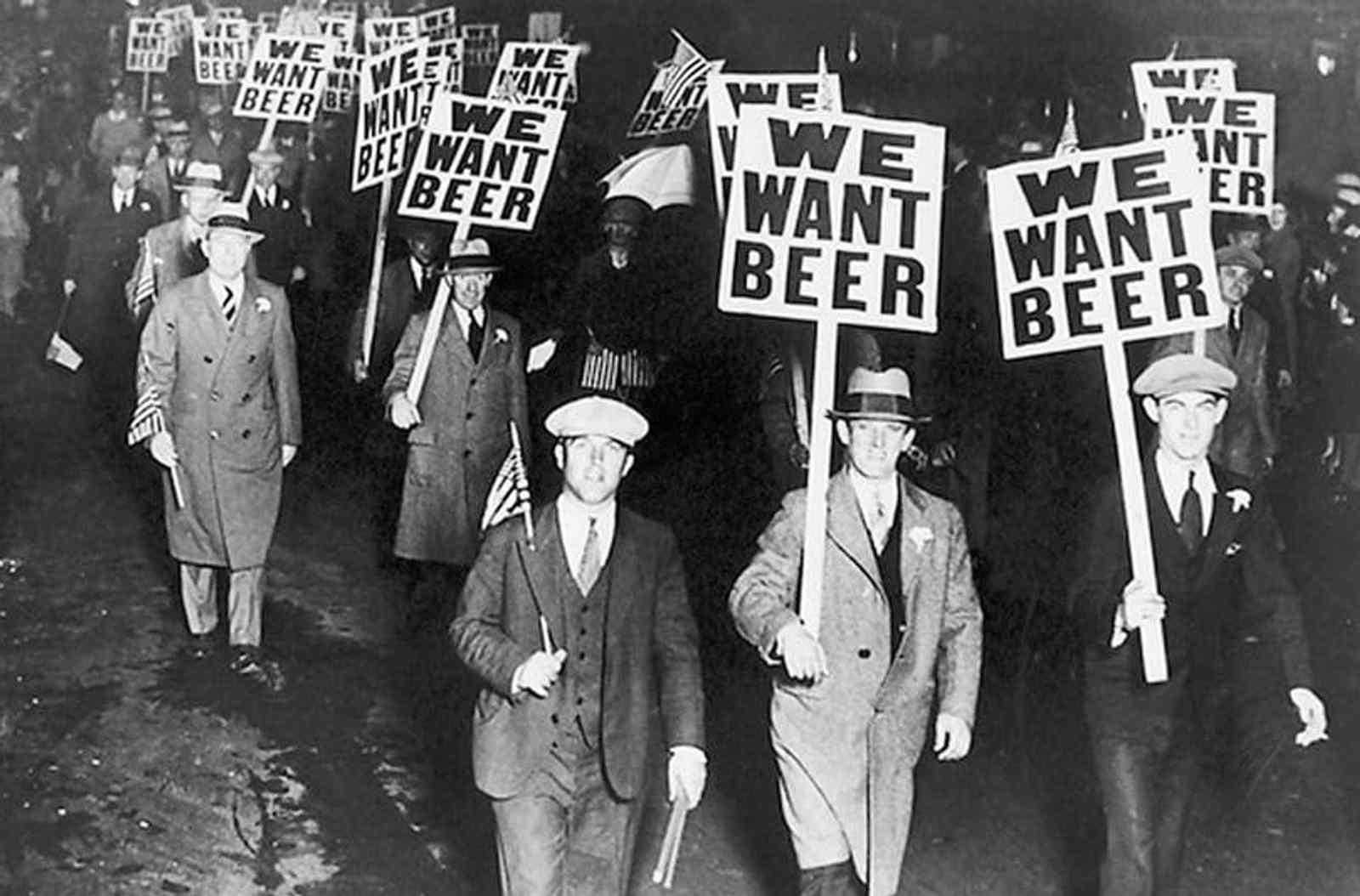

It was the roaring twenties and alcohol prohibition in the U.S. meant an increasing interest in Canadian booze. During the American prohibition, the production, importation, transportation, and sale of alcoholic beverages was banned from 1920 to 1933.

Many men from South-Eastern Ontario turned to alcohol smuggling—or ‘rum running’—to make a pretty penny; they could make more money in a week of alcohol smuggling than in a whole year of fishing.

Did You Know?

Main Duck Island, a small island located off the coast of Kingston, Ontario, was a prominent location for prohibition era rum running. The island was an exceptionally popular stopover spot for alcohol smugglers. Today, it is part of the Thousand Islands National Park.

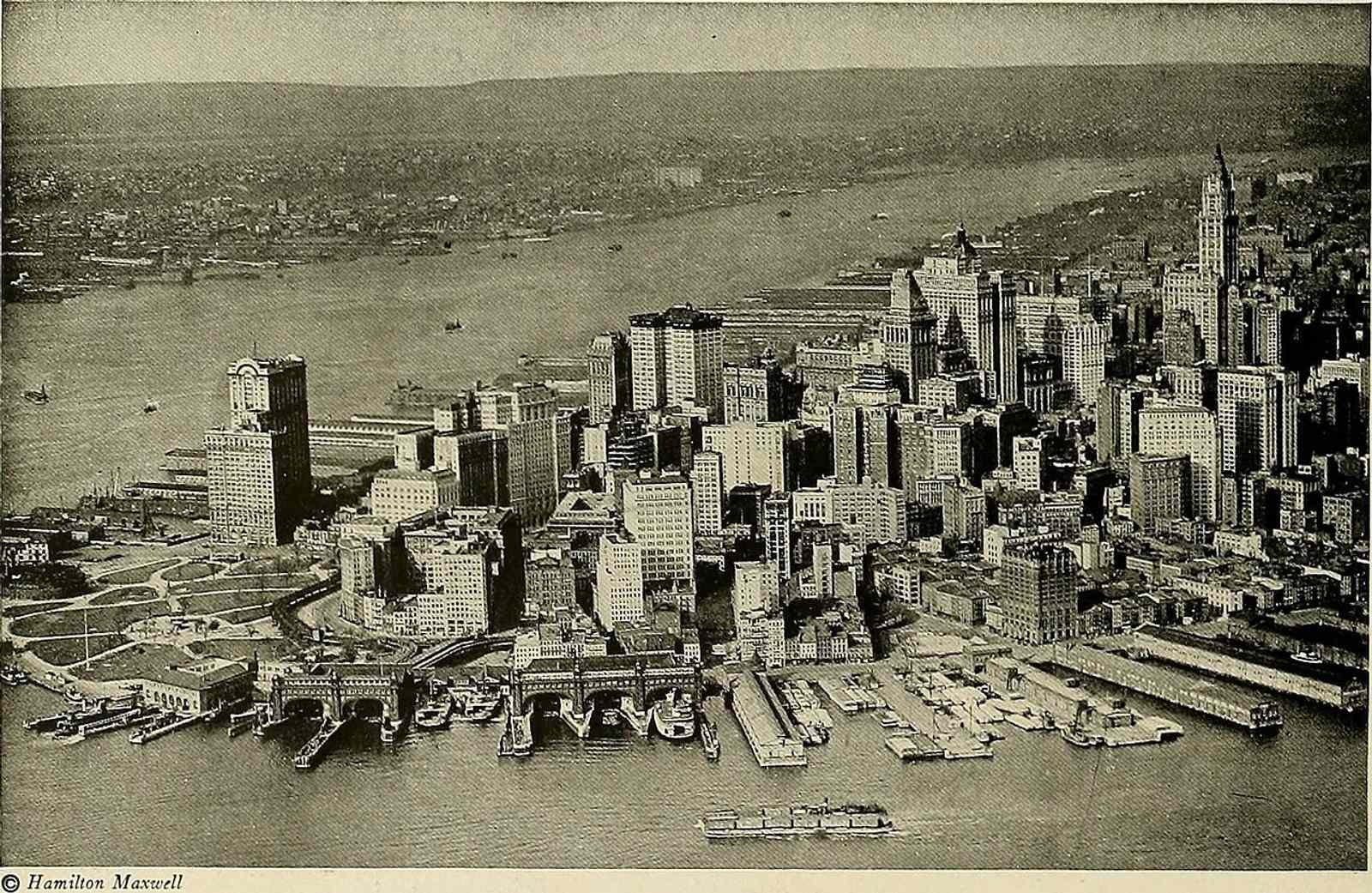

Main Duck Island occupied prime real-estate for smuggling due to its position between Long Point Harbour (at the southeastern tip of Prince Edward county) and the American border (between Vermont and New York). Even better still, the island was well-hidden from view from authorities.

During the 1920’s, the island was owned by an infamous smuggler: Claude “King” Cole from Cape Vincent, New York. In 1904, Cole purchased the island from the Government of Canada for a mere $1,200 (which would be about $36,000 today).

Cole owned Main Duck Island from July 14, 1905 to May 13, 1938. Shortly thereafter, John Foster Dulles (the US Secretary of State for Dwight D. Eisenhower) purchased Main Duck Island in 1941.

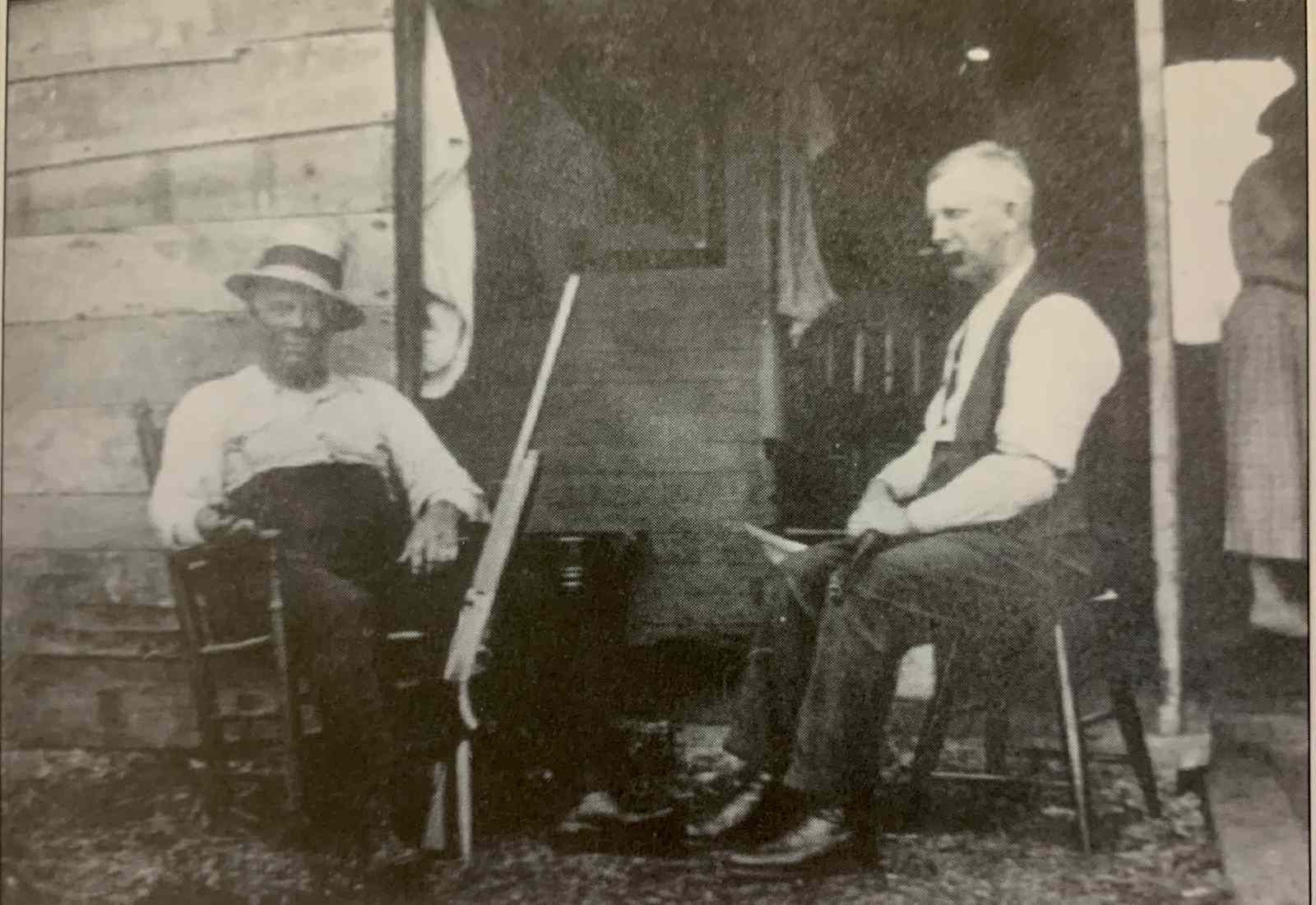

During Cole’s time owning the island, its primary residents were a small colony of fishermen, the lighthouse keeper and his family, and Claude “King” Cole himself.

Cole was not exactly what one might imagine when picturing a notorious rum runner.

He was a man in his fifties during his smuggling days, a grandfather, and an esteemed member of the island community. That said, he did have a reputation as a risk-taker –– someone who was unafraid of (and perhaps even enjoyed) danger. He was also considered sociable, outgoing, and a fantastic storyteller.

However, Cole's personality was multifaceted and he was also known for being highly dogmatic. He ran a tight ship on the island, and had no qualms about banning anyone who he felt had wronged him.

Nevertheless, he was widely well-liked, and at the very least, respected and admired by others for his business savvy and his boldness in all of his endeavours.

Cole had many other successful businesses before, and during, his rum running days.

Before coming to Main Duck Island, he was a farmer in the Milford region. After purchasing the island, he built himself a two-storey farm house as well as some fishing huts which he rented out to commercial fishermen. His swanky residence on the island was much more luxurious than the cabins and huts of the fishing village.

In his early days on the island, Cole occupied his time by managing fishing industries and looking after his livestock, including hogs, sheep, horses, cattle, and even a few buffalo. Cole bred racehorses, and it was actually his involvement in horse racing that led him to the same circles as those who ran speakeasies.

Did You Know?

When manufacturing and selling alcoholic beverages was prohibited in 1917 with the Volstead Act, Cole heard the knock of financial opportunity. He became an alcohol smuggler—as did many other enterprising Canadians during the era.

Just as many Canadian provinces were deciding to end prohibition legislation, the United States was introducing its own. Right as Canadians regained permission both to manufacture and export liquor, a market for bootleg booze was opening across the border. Alcohol had become as good as gold!

Legislation surrounding prohibition were complex, but one thing was certain: rum runners were not actually breaking any Canadian laws by using Main Duck Island as a home base (so long as they travelled straight to their foreign destinations from their Canadian harbour).

Under the Ontario Temperance Act, it was the off-loading and storing of the liquor that was illegal.

Cole bought enormous amounts of Whisky from the Corby distillery, as well as beer from the Belleville brewery and Old Tower beer from Kingston. He would transport up to 1000 cases of alcohol to Main Duck Island on his cruising yacht, the Emily.

This common contraband was stashed carefully in the old stone houses on the island, hidden from prying eyes and kept safe until it was time to transport it. When the time came, Cole would then distribute the alcohol among the nearby commercial fishing crews.

During the fishing season, the fishermen who rented huts on Main Duck Island would covertly smuggle alcohol into America alongside their day’s catches.

Sometimes, Cole himself would take the Emily and its cargo of contraband across Lake Ontario, travelling first to Oswego and then to Syracuse, greasing the palms of various canal and customs officers along the way to ensure his safe passage.

At times, up to seven or eight rum runners at a time would seek shelter in the island’s small harbour, and some nights as many as six ships would be anchored, standing by, waiting and ready to make the trip to the States.

The island provided the perfect shelter for the rum runners to wait for the cover of nightfall before dashing across Lake Ontario’s watery ‘highway’ to the American border, bringing their illicit cargo to a thirsty and booze-less public.

In bad weather conditions, smugglers would often stay the night on Main Duck Island in one of the fisherman’s huts, where they would pass time playing poker, drinking, and weaving tales of death, detainment, and close calls with the cops.

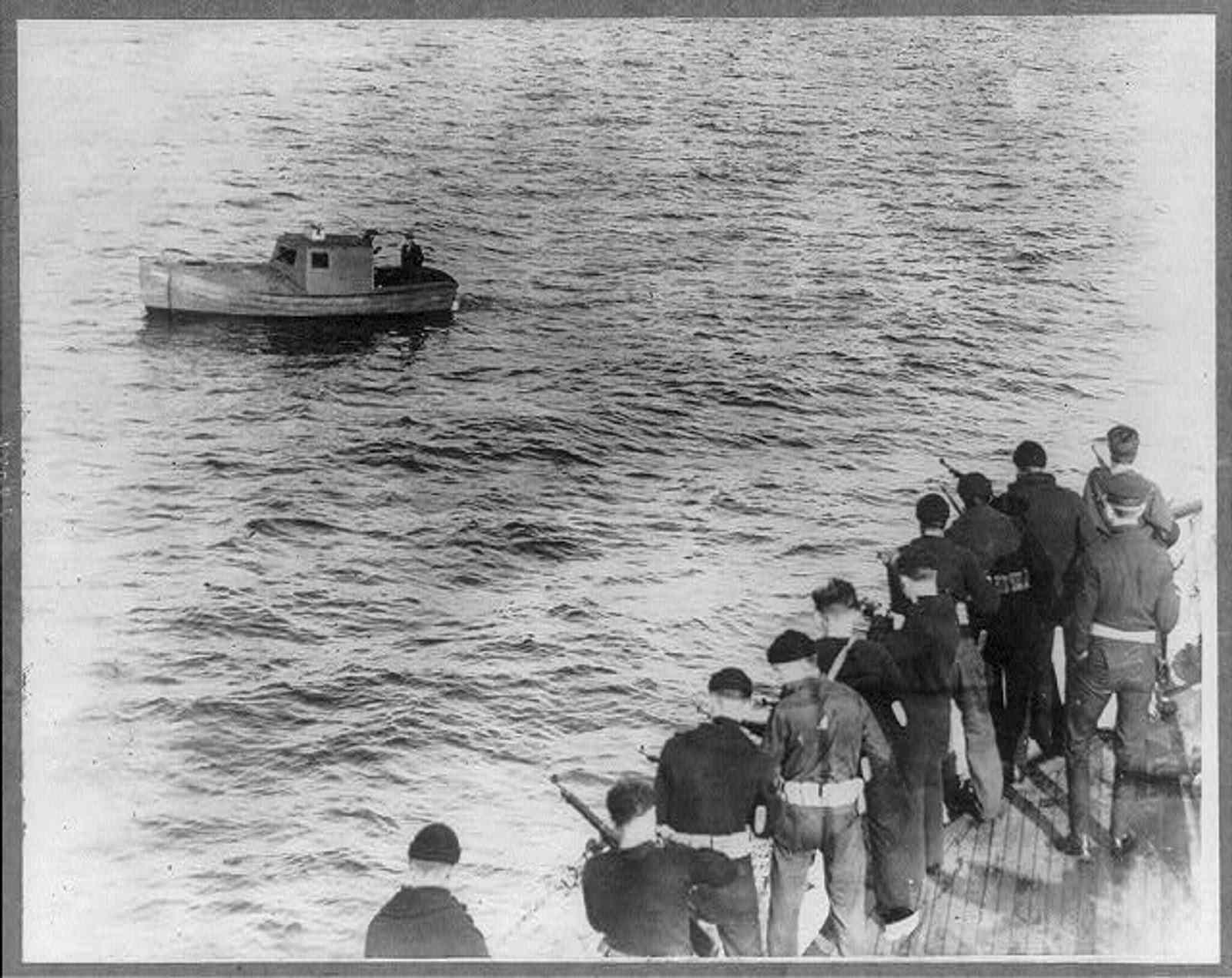

Such ventures were lucrative, but risky, and penalties for those caught were harsh.

Rum runners would even go so far as to hide the heavy glass bottles of alcohol in flour and potato sacks so that they could be dumped into the lake and would sink to the bottom if the authorities were hot on the trail.

When the danger of being caught had passed, the rum runners would then pull the sacks back up by dragging for the lines that were connected to the weighty bags and continue their expedition.

Whenever the coast was clear, the smugglers would dart across the waters—a perilous trip when there were wavy or icy conditions—often having to flee from and outmaneuver the gauntlet of United States Coast Guard vessels armed with powerful weaponry and a vendetta against the brazen bootleggers.

Did You Know?

Cole’s business was booming, but in 1921, the Belleville and Ontario Provincial Police officers performed a raid on his criminal operations on Main Duck Island.

The raid was led by License Inspector Frank Naphan, accompanied by Sergeant Dan Boyd of the Belleville police and two Ontario Provincial Police officers. It was the first rum running raid by authorities on Lake Ontario.

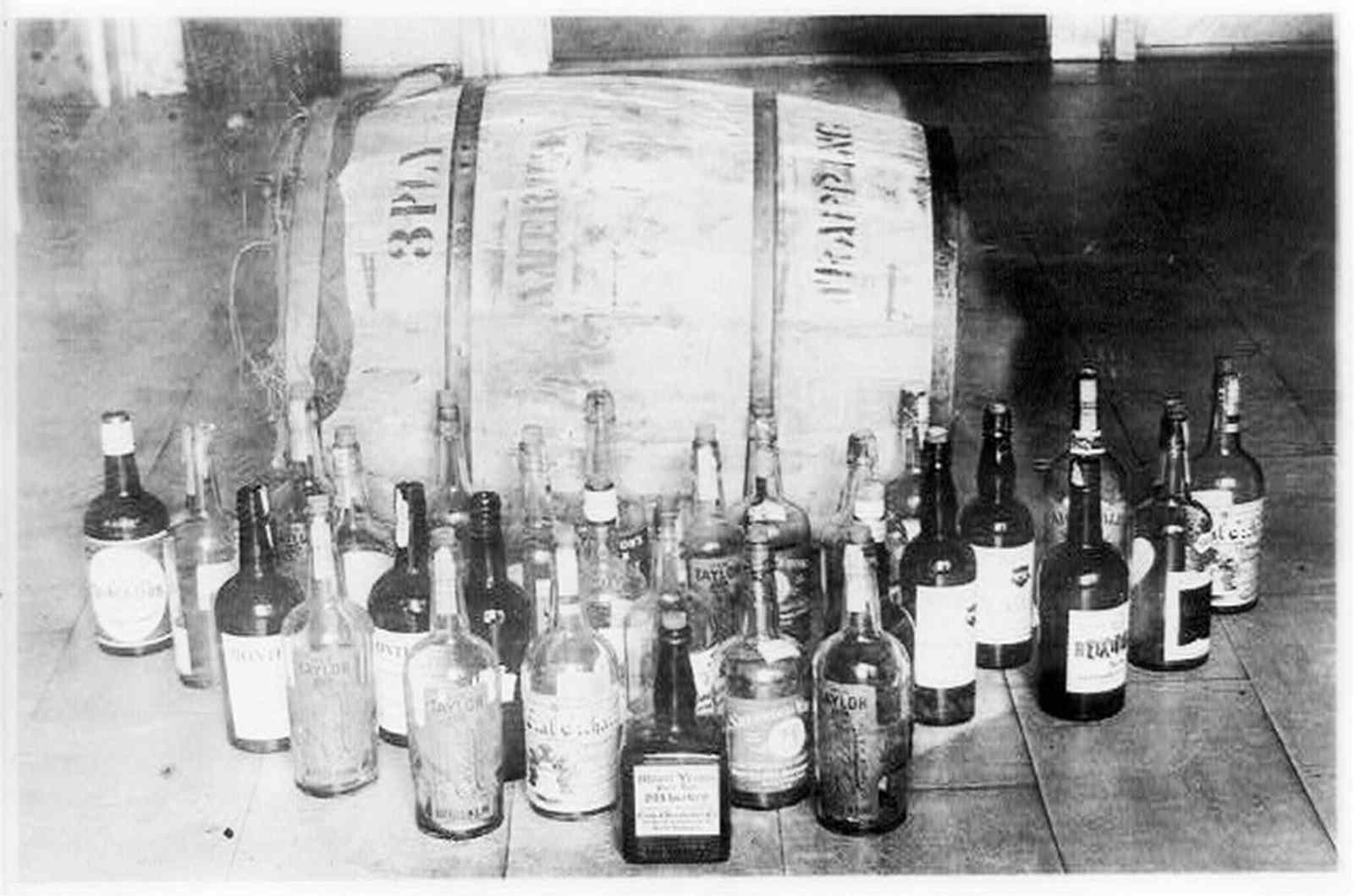

Naphan was initially unable to find contraband in Cole’s house. But upon searching a nearby dilapidated stone structure (also belonging to Cole), his efforts were rewarded. Using a crowbar to pry open the door, Naphan found stockpiled wooden boxes that reached up to the ceiling flagrantly labelled ‘Old Kentucky bourbon’.

In sum, there were 32 cases of bourbon, 10 gallons of rye, and 10 gallons of straight alcohol! Naphan confiscated the alcohol, no doubt feeling proud about having carried out the largest scale seizure of illicit alcohol on Lake Ontario to date at that time. He brought the booze to Picton, where Cole’s trial was to be held.

Cole’s trial was a spectacle.

Many came to watch, both Americans and Canadians, journalists and farmers alike. Cole appeared at ease at the trial, his defence being that he had amassed the alcohol in question for personal consumption, and had therefore not committed a crime.

Fortunately for Cole, Lady Luck was with him at the trial. The Picton magistrate ruled in favour of the bootlegging ‘King,’ citing that Cole was within his rights in owning more than one residence and in filling one of them with liquor.

Cole's case was dismissed, and the confiscated alcohol was returned to him on Main Duck Island, likely to end up in the bellies of our friends across the border.

Eventually, rum running dried up in the early 1930s with the end of Prohibition in the United States, but Main Duck Island on Lake Ontario remains a site of historical significance from its time as a homebase and a haven for bootleggers.

Cole died in 1938, still regarded as the “King of Main Duck,”. He lived on in the memory of all who had known him (or even those who had merely known of him) as one of the first and most prosperous smugglers during prohibition... and, of course, as a Lake Ontario legend.