Published May 27, 2020

Bryan was born in Coventry, England, in the Midlands. His father was from Tyneside, northeast England, and he would go to the seaside there every summer. The water was cold in the North Sea, so they didn’t often swim. As a child, Bryan was afraid of the water, but learned to swim when he was 9 years old.

Bryan learned to swim with the help of an uncle who would take him to the local swimming pool every weekend. His uncle wanted him to learn front crawl, so he was most disappointed when Bryan started doing breaststroke all the time.

His uncle would say “Every time I see you do breaststroke, you’re going to go off the 3 meter diving board.” And so, Bryan became accustomed to jumping off the 3 meter diving board.

Bryan’s love of swimming grew quickly after that. He often swam in a local open air pool and in the wild waters of the lake district. A true fish in the water, his friends struggle to get him out of the pool. To this day, Bryan can’t be sure if his friends were worried about him, or if they were simply embarrassed that he was outshining them in the water.

When Bryan was in grammar school, he spent his lunch time at the swimming pool. He joined a local swimming club where his exceptional swimming abilities were discovered. A coach told him, “Wow, I think you’re faster than the representative that we’re going to be sending for Coventry to the Midland school championships!”

Bryan was too late for the championships, but ended up beating the swimmer who won them in a 100 yard swim off.

After that, Bryan got some special training facilities. He spent half an hour training on weeknights, and two hours training on the weekend.

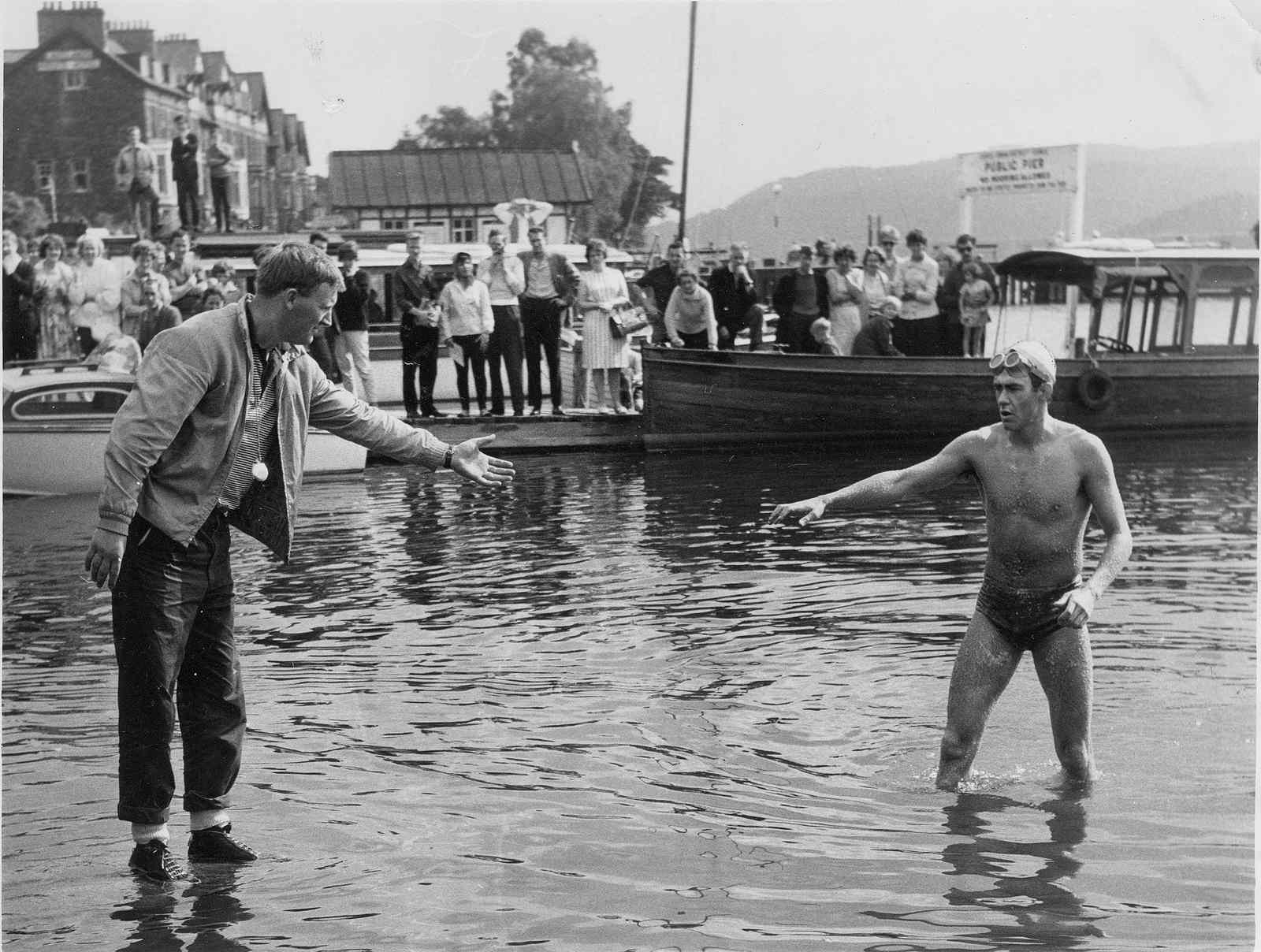

In 1960, Bryan became even more serious about open water swimming. The Windermere Championship was approaching. It was just over a 10 mile race, and it was the biggest event of the year for the British Long Distance Swimming Association.

He practiced for the race with his friend Peter Fergus leading up to the Windermere Championship. The two swam the length of Coniston, a 5-mile swim, as Peter taught Bryan how to pace himself.

As they swam, Bryan kept pace with Peter. But as they neared the final bend towards the finishing point, Peter stuck his head down, started kicking, and sped off. It took effort, but Bryan stayed with him the whole way.

“We broke the record for that swim by 10 minutes. We made it in 3 hours, exactly. And that wasn’t good for me, because I got it into my mind that I could break records.”

The following week was the Windermere Championship. Bryan swam valiantly, fighting hypothermia, and placed 4th man overall against the freestylers. While he just missed the breast stroke record that year, he would go on to take the record two years later in 1963.

Bryan has set many records over his long open water swimming career. Many still stand today.

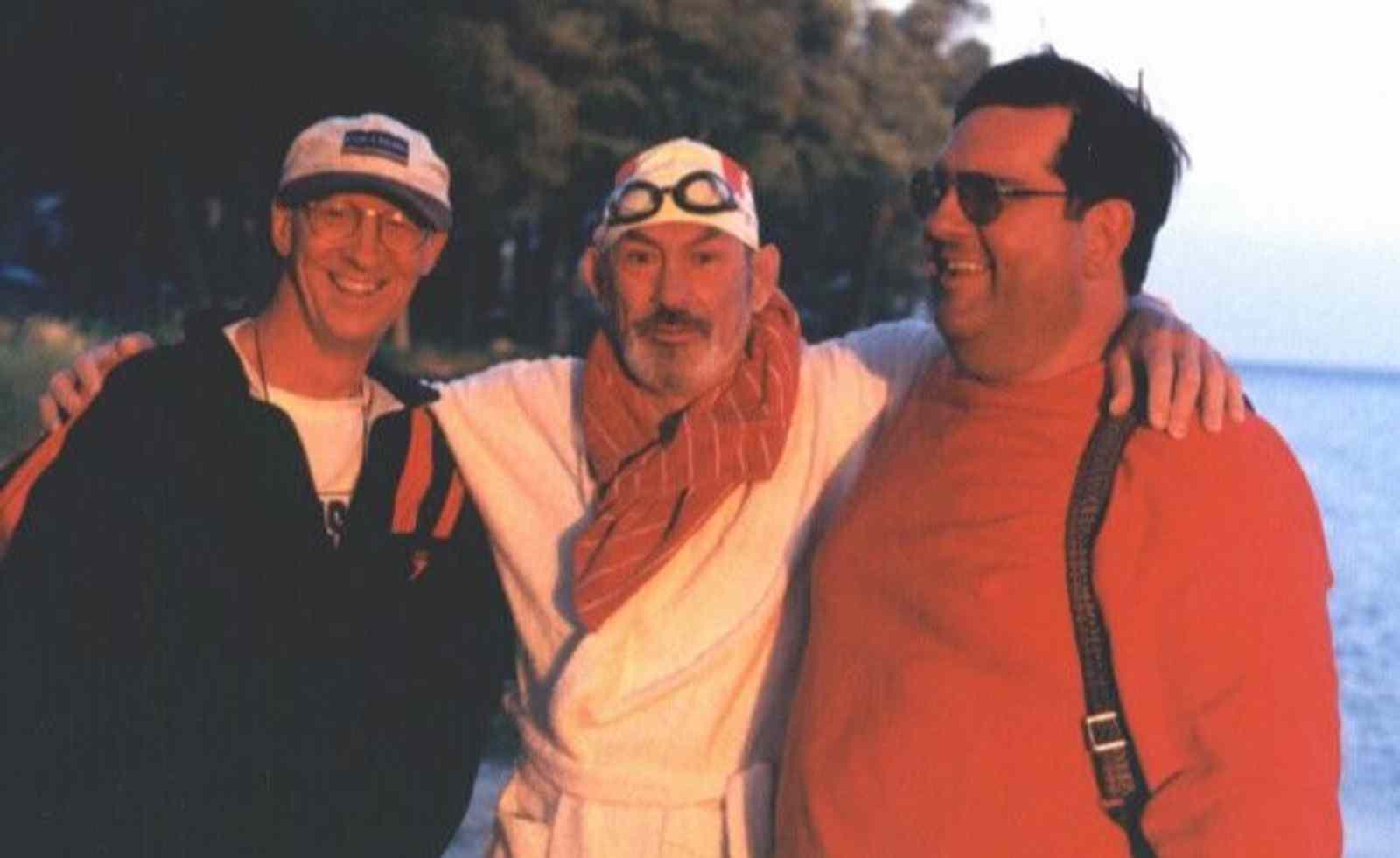

Bryan’s standing records include: the Fleetwood-Morecambe swim in 1966, Coniston 2-way crossing in 1983, Lake Simcoe crossing in 1999, and Lake Erie crossing in 2001.

Step inside the mind of an open water swimmer

What does an open water swimmer think about for all those hours? Initially, Bryan says a swimmer is probably thinking of the first feed, or looking at the sunset, or some other thing that might offer a distraction. He might be thinking, “Maybe I didn’t put enough grease under my arm and it's starting to chafe.”

A variety of odd things like that might go through a swimmer’s mind at the beginning. These thoughts can last up to the first couple of hours or so.

Thinking about your own safety is also a concern for swimmers embarking on certain swims. Swimming in Lake Ontario, for example, there are many things you have to keep at the front of your mind.

If you’re starting your Lake Ontario swim at Niagara on the Lake, you’re going to have to traverse ‘the rapids’ (the fast flow of the Niagara River). According to Bryan, the water there is all over the place. These are the times when you need to be aware of your surroundings and mentally alert, he says. It’s very easy to pull a muscle in the first half hour of a Lake Ontario swim.

It takes a while to settle your mind down.

“Beyond that time, hopefully, you settle into it and you can relax your mind. Open water swimmers can close our eyes. We don’t have to watch for every little rock so we don’t twist our ankles or fall over like runners do. We can let our minds go.”

You can tune out, swimming in a lake or ocean. In some ways, Bryan says, you actually don’t want to focus on the swim. It’s an incredible feature of the sport that you can close your eyes and get some relaxation.

Swimming in Lake Huron

Bryan has spent a lot of time training in Lake Huron. One route he particularly likes is Port Franks to Kettle Point, a 5 mile journey. He did this swim as a 10 mile training session about two or three times along the shoreline. Another training swim he liked was from Port Franks to Grand Bend, also a 10-miler.

He intended his swims in Lake Huron as training for a crossing of Lake Ontario in 1992. Although he didn’t make it all the way across, few can say that they have attempted the daring feat.

When Bryan began the trip across Lake Ontario, it was a fairly warm day. But as night fell, so did the temperatures. He had already been in the water for eight hours, if not more.

Each time he did his breaststroke, he could feel the frigid water running down his back. He recalls that there are some sensations that you can only put up with for so long. On the flip side, Bryan believes there’s a tremendous sense of achievement after you’ve controlled your mind to withstand the challenges of open water swimming, like cold water.

Swimming in Lake Simcoe

Bryan’s longest swim took place in Lake Simcoe and lasted 21 hours. It took three attempts before he managed to make it all the way across.

During his first attempt, lightning began rolling in after only 10 miles. At first, Bryan refused to get out of the water, determined to complete the swim. As the lightning got worse, bright flashes shot across the sky, and he eventually got out of the water.

There comes a time when safety is more important than success.

His second attempt went better. This time, he made it about 14 hours into the swim. He was coming out of Kempenfelt Bay, heading up the long stretch before reaching the final bay into Orillia. There was a following wind and he was surfing along with the waves. He remembers thinking, “This feels so great!”

Bryan was kicking and pushing and using the waves to propel himself forward–it was a wonderful feeling. But in his exhilaration, he began to kick harder and harder. He didn’t realize how much his exertion was taking out of him.

He got around the bend and into the bay heading into Orillia. The muscles in his forearms were burning with every stroke. Normally, in training, a swimmer will swim with such pain for an hour or during a 200 meter race. But to put up with that for three hours? Well, that’s a different story. Bryan says that he’s never felt that excruciation since.

Bryan began slowing down. His arms were killing him, he remembers Bob Weir, who was in his boat, saying, “Look, I’m not going to take you out. You’re going to swim to the side of the lake. You’re not going to make it to the finish today.” Bob said afterwards, “If it had been Lake Ontario, I would have kept you in there.”

Bryan began swimming to shore, ending up on a stranger’s property. Luckily, the man was friendly. He came down with a snowsuit for Bryan to put on to warm up.

The next year, Bryan made his third attempt.

He reached the long stretch after exiting Kempenfelt Bay, the very spot where he’d been surging along with the waves during his previous attempt. This time, the waves were against him.

Bryan settled into a steady pace and persisted into the final bay. About halfway down the shore, he saw a boat. In an astonishing coincidence, it was the man from the property where Bryan had gotten out the year before! This time, Bryan passed the man’s property, going on to successfully complete the swim.

Swimming in Lake Erie

In 2008 at the age of 51, Bryan swam from Leamington to Pelee Island on Lake Erie, accompanied by his son.

This swim in particular stands out in Bryan’s mind as an achievement. And it should. Despite battling hordes of living and dead shad flies as well as the waves from four freighters, Bryan’s time of 10:44 broke the Free record for the Leamington to Pelee Island swim of 22.1 kilometers.

Threats to the Great Lakes

As someone who swims in the Great Lakes, Bryan has noticed the threats to them over the years.

Lake Ontario swimmers used to worry about the water coming down the Don River after a big flood or heavy rainstorm. They would have to battle the force of the water pushing past Toronto Island trying to make it to Marilyn Bell park.

Bryan notes that he also had to swim through the grunge and anything else that was washing off the streets.

Bryan has also felt the concern about Lake Ontario’s lamprey, an invasive species. Bryan has heard stories of them attaching to people. When they’re pulled off and thrown away and there are marks on a person’s body when they come out afterwards. Lamprey harm other aquatic life as well.

Bryan also laments the blue-green algae at the western end of Lake Erie, created by agricultural runoff from farmer’s fields in the summer. Blue-green algae is a danger to swimmers that has only increased over the years as warmer water temperatures are further aggravating its production.

At present, Bryan also notes that high water levels are another major problem on Lake Huron and Lake Erie, and that they have been an issue in the past as well.

Bryan’s home beaches

One of Bryan’s favourite Great Lake beaches is the beach at Port Franks. The beach is at the outlet of Mud Creek, a small river that comes around the back of where Bryan lives. It’s a shallow area. In the winter, there are big, beautiful buildups of ice and sand.

During the summer months, the beach is a bit too crowded for Bryan to enjoy. The beach belongs to the property owners, but it is very popular. Everybody tries to go there. It’s restricted access in a way, because there are only about 10 parking spaces.

Another one of Bryan’s favourite Great Lake destinations is Port Stanley, Lake Erie. He used to do six hour training swims there for the English Channel swim. The beach has a big roped-off area, probably about 400 meters in length. You can swim out along the buoy line by yourself without the fear of power boats or jet skis. Bryan really enjoyed his trips swimming there.

What Bryan likes best about open water swimming

Many coaches would rather not tell the swimmer how they’re doing, or how far they’ve got left to go. But as a swimmer, Bryan really relies on that information.

Bryan is a breastroker, which means that in open waters, he’s a bit like his own pilot. He can see the end of the lake and calculate the distance left to travel.

“In the pool, I watch the clock. I’m a clock-watcher. I’m a statistics man, a numbers man. But I do enjoy seeing the scenery in open waters and being in control of setting my course. I’m lining up a particular point with that spike on the mountain so that I keep myself on course. I’m not totally reliant on the kayak that’s next to me.”

During a swim Bryan can tell that, for example, he has two miles left, and he’s doing 25 strokes a minute, his next feed is in half an hour, and he’s got 750 strokes to go. Thinking those thoughts drive him on. Plus, he’s got the beauty of the lake to enjoy because he’s keeping his head out of the water, doing breaststroke.

Bryan now lives in London, Ontario, and also has a place at Port Franks on the southern shore of Lake Huron just below Grand Bend. He’s grateful for the long-time support of his family, friends, and mentors over the years.

As you can probably guess from his love of statistics, Bryan has worked as a mechanical engineer. His work has focussed on automatic control systems, orthopaedics, and respiratory work.

To learn more about Bryan’s home beaches, visit them on Swim Guide here and here.

Learn 3 things to remember for open water swimming here.

Read our other open water swimmer profiles here:

Open water swimmer profile: Jessi Lidstone Harewicz

Open water swimmer profile: Robert McGlashan

Open water swimmer profile: Mauro Campanelli

Open water swimmer profile: Catherine McKenna

Open water swimming profile: Greg Maitinsky